- Ukrainian Americans are reeling after Russia began its invasion on Wednesday night.

- Many repeatedly check in with family or friends in Ukraine, but feel powerless to help them.

- Ukrainian Americans in California told Insider how they're coping with the first days of war.

SAN FRANCISCO, LOS ANGELES — Roman Trofymenko's phone erupted in notifications on Wednesday night.

His friends in Ukraine were posting on social media about loud booms they heard in the distance — missiles and bombs Russia was launching at airports and military bases across the country. In Kyiv, Ukraine, it was a few minutes after 5 a.m. Thursday. Russia was beginning its invasion.

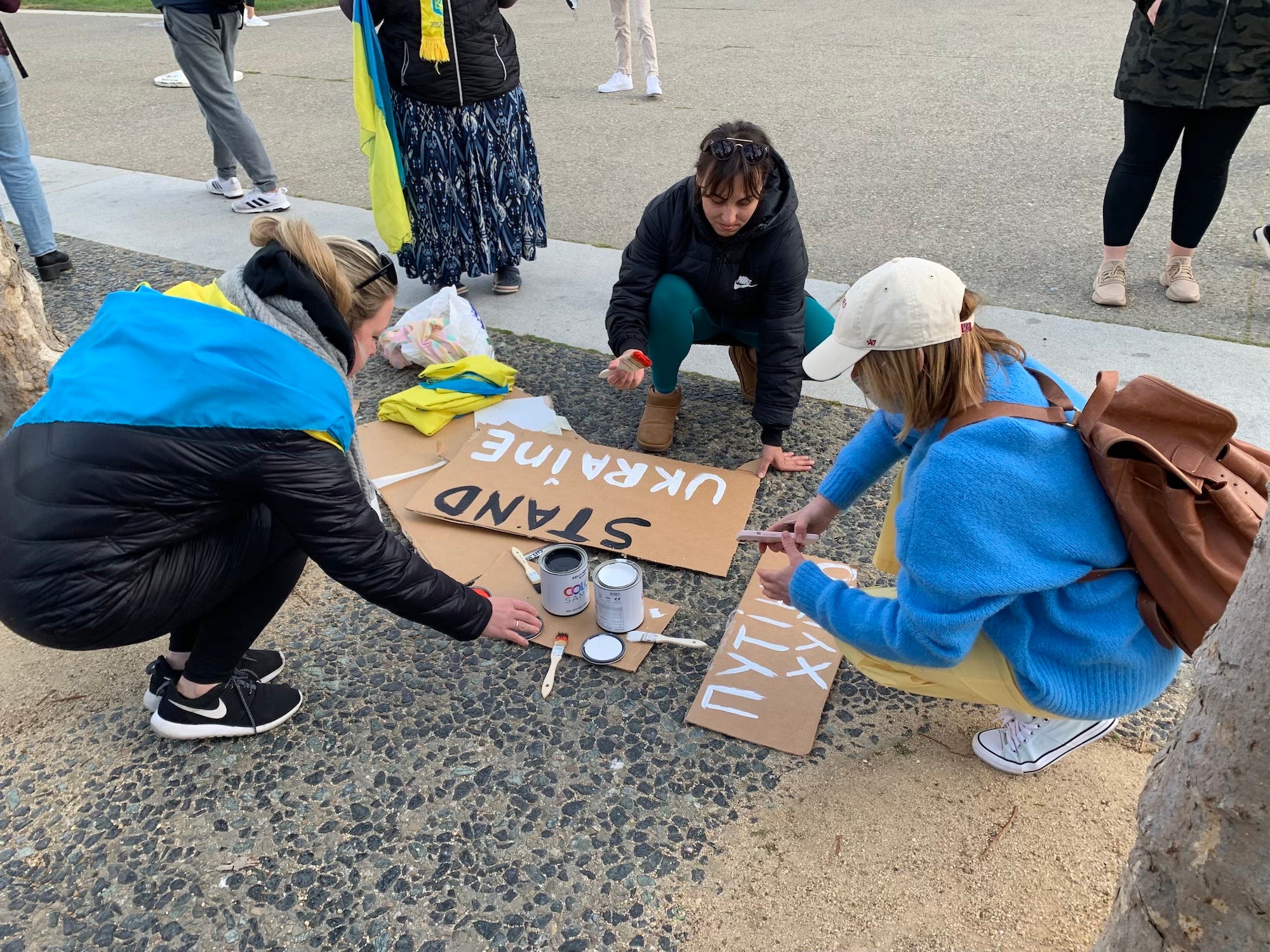

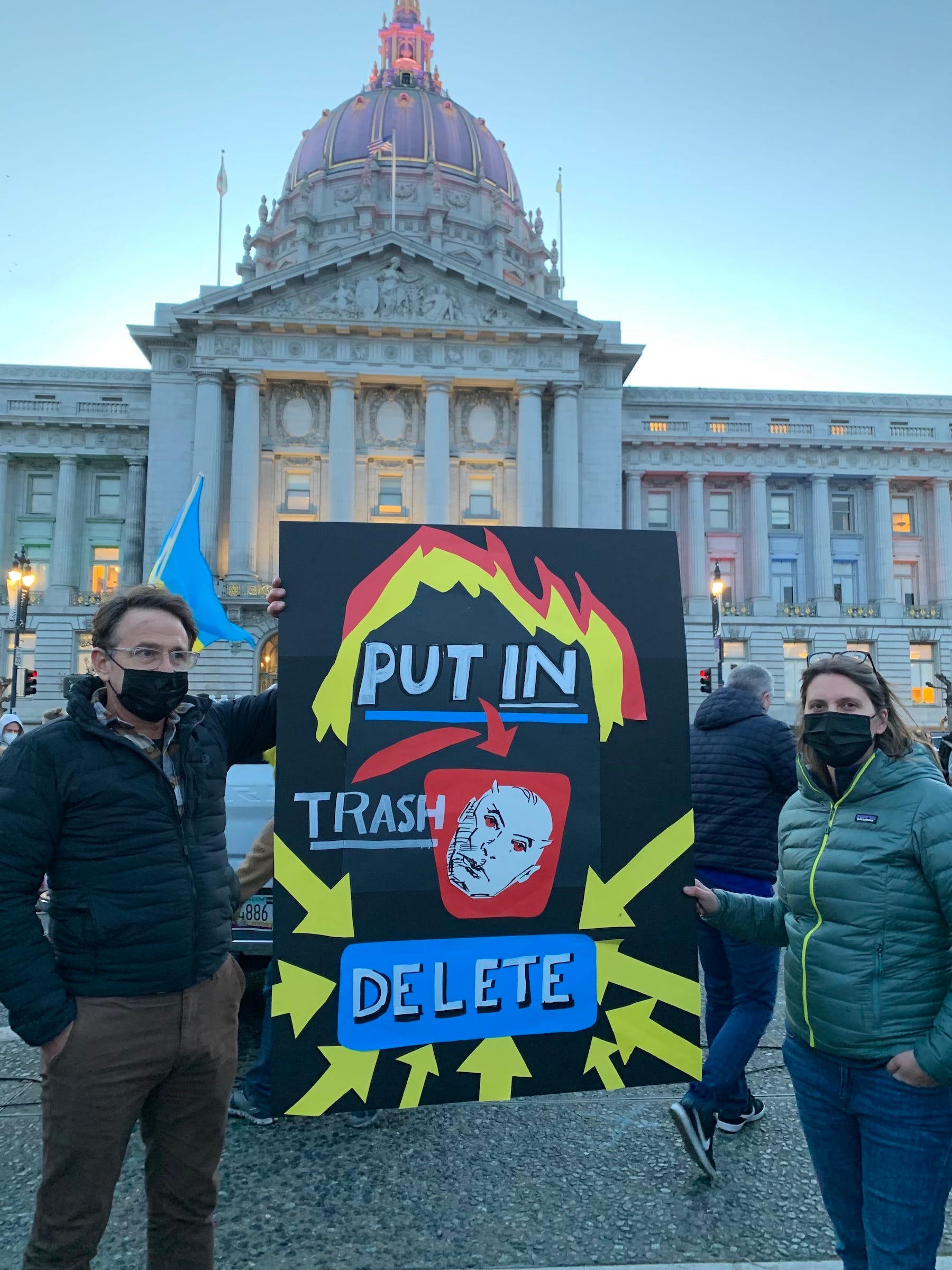

Within 24 hours, Trofymenko and his wife, Tanya, who declined to share her last name, were with about 1,000 others at an anti-war protest in front of San Francisco City Hall. Demonstrators waved blue-and-yellow Ukrainian flags and sang the country's national anthem. Tanya's homemade sign read "Drink shit, Putin," in Russian.

"Yeah it's very aggressive," she said of her sign, but Trofymenko added, "It's not as aggressive as shelling civilian buildings."

The protesters had demands — enact sanctions, cut Russia off from SWIFT, and send military and humanitarian aid to Ukraine. But for many Ukrainian Americans who attended, it was a chance to gather with others who shared their fear and despair, who were worried for loved ones stuck in Ukraine's seiged cities, and who could do little else to help.

"It's taken lots of anti-anxiety medication to stay sane," Olena Polovynkina, who has family in Kyiv, told Insider. She drove two hours with her mother, husband, and twin babies to attend the San Francisco protest. "Really sad. Really angry. Really helpless. A spectrum of emotions. It's just terrible to watch and see people die."

In Los Angeles, another group of Ukrainian Americans gathered for a vigil at the Nativity of Blessed Virgin Mary Ukrainian Catholic Church. They sang hymns and prayed. During the Thursday evening service, Ukraine faced a second consecutive night of Russian bombardment.

"For a couple of hours, I was in such a shock that I could not believe that it happened," Rev. Ihor Koshyk told his congregation, adding, "It felt to me as if I was sleeping and it was not real."

"Gathering together helps us to deal with our anxiety, it brings us a little bit of comfort," he said.

Using anti-anxiety medication and vodka to cope

Polovynkina and her mother, Tetiana, began shaking uncontrollably when they heard the first reports of bombing in Ukraine Wednesday night.

"I was hoping it was a joke until then," Polovynkina said. "It was a really strong stress and anxiety reaction. I never experienced it in my life. We were both really cold and shaken up."

They stayed up late watching the news, trying to track Russia's movements across their home country.

"We can't put our computers down. It's just horrible. Your heart is breaking, basically," she said.

Polovynkina needed anti-anxiety medication to get to sleep that night.

A demonstrator named Sergey, who only gave his first name, told Insider that his family and friends in Ukraine are being advised to cover their windows in duct tape, so that shattered glass won't fall into the house.

"The idea that they are suffering — like right now they are waiting [for] bombs and I'm not — I feel ashamed and feel this guilt that I'm not there," Anastasia K., who said she's been coping by "drinking a lot of vodka," told Insider. She declined to give her full name.

"The biggest fear is my people die. People die and my country will die and will be burning," she added. "Even if somehow we win, what will be left? Ruins. Just ruins and dead people. And for what? I just can't understand for what."

Many feel powerless to help their family and friends in Ukraine

Anastasiia, who declined to share her last name to protect her privacy, returned from a visit to Ukraine just two weeks ago. On Thursday, her parents were hunkering in a bomb shelter in Kyiv. When she first heard reports of bombing, she called them, but they couldn't talk. They were rushing to pack their suitcases.

"I'm not available for them. I feel helpless," she told Insider, adding, "Maybe I missed the signs. I don't know."

Polovynkina has been talking to her family regularly, but the conversations are difficult. They've ended up talking about the babies to avoid discussing the conflict.

"No one knows what to say. No one knows how to support each other," she said.

For now, her family is stuck at their home in Kyiv. They have no plans to leave.

"They say they don't want to be refugees. They'll stay to the end, whatever that is," she added.

Back in Los Angeles, Rev. Koshyk said his parents and dozens of relatives who live around Lviv were considering fleeing to Poland.

Natalia, a churchgoer with grandparents, siblings, and cousins in Starokostyantyniv, western Ukraine, said that her mother simply asked her to pray. On Wednesday night, Natalia's sister called her, saying she could hear explosions.

"They went to the basement of their building with mattresses for the night," she told Insider. "My grandma told my nephew to help her put together an emergency medical kit and he told her 'Grandma, I'm scared,' and couldn't eat that night."

Natalia declined to share her last name out of fear for her family's safety.

In a phone call on Friday, Trofymenko said he felt more hopeful than he was at the Thursday protest.

"I see a lot of reports specifically from Ukrainian military, and they're quite optimistic, so I'm trying to stay optimistic as well. Overall, we are more enraged than depressed," he said.

Struggling to explain war to young children

Nadia and Josh don't know how to explain the situation to their three young children, who are under the age of 7. They declined to share their last name, to protect family members in Russia and Ukraine.

When they said they were going to the San Francisco protest, their daughter asked, "Is this a holiday? Are you celebrating [Putin's] birthday?" Josh told Insider. "And we explained, 'No, we're not. We're doing this so people tell him to stop.'"

Nadia grew up in Russia, but her sister lives in Odesa, Ukraine, with her own family. Her sister's husband and two 20-something sons can't leave the country, since the government banned all male citizens 18-60 years old from leaving. On Thursday, her sister used the phrase: "If we survive."

"I've been mostly crying," Nadia said, tears filling her eyes. "We didn't want this war. None of us. But no one gave us a choice."